Python Sockets and Async

Sockets

Sockets were started at Berkeley in the 80's, and basically became the standard for network communication protocols - a socket is an abstract representation or the local endpoint of a network communication path

The Berkeley sockets API represents this as a file descriptor in Unix, and it provides a common interface for input and output to streams of data

Reusing file descriptors was smart as it builds on top of already created Unix interfaces, and essentially allows you to interact with incoming and outgoing data as if it were coming into and out of a file

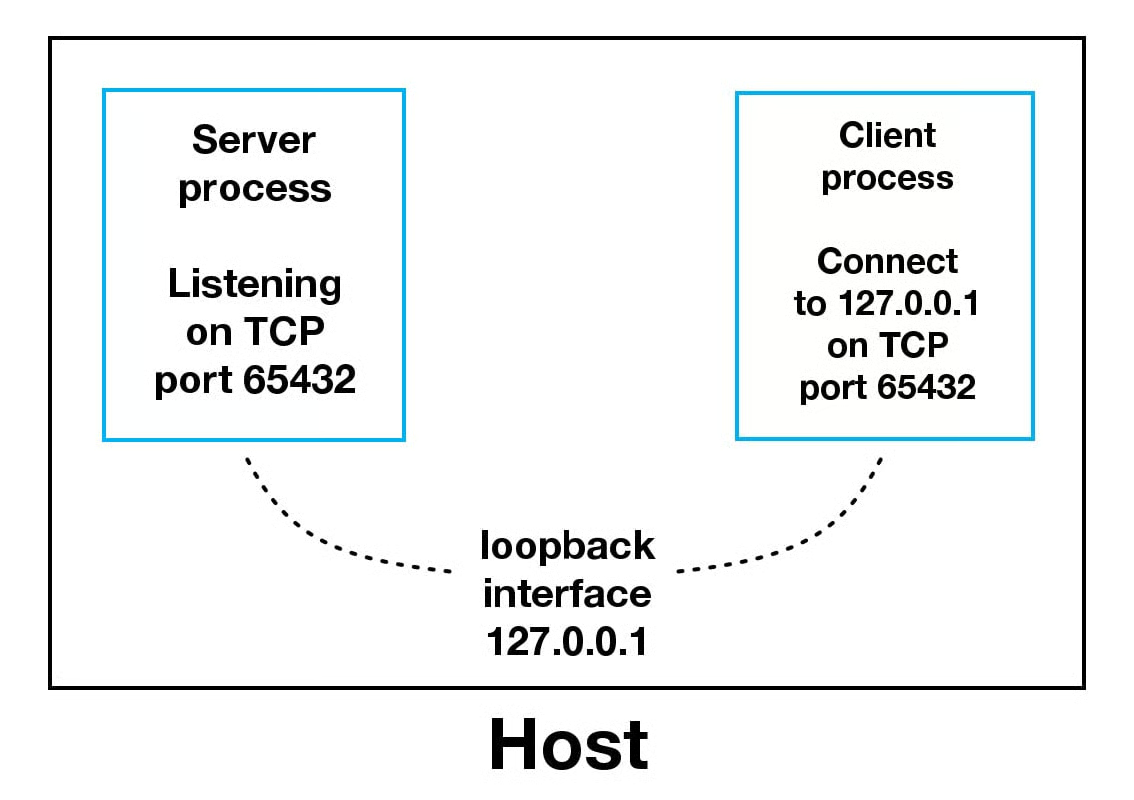

A socket is an abstraction over IP:port so that 127.0.0.1:4000 is us itilizing port 4000 on our local IP address - we can interact with this specific identifier and reach process(es) listening on that port

There are blocking and non-blocking ways of working where you either wait for things to complete (blocking) or you continue working (non-blocking). They also allow specifying L3 level protocols like TCP vs UDP, and most socket API's can interact with all of these lower level protocols

In Python sockets allow for inter-process communication over networks, and it's the backing of most common networking frameworks like AsyncIO, FastAPI, and Uvicorn which all typically build on top of sockets to achieve concurrency using non-blocking asynchronous techniques. The reason this is so vital in Python is that Python is single threaded (due to GIL interpretation), and so building API's and utilizing all cores on a VM is increasingly important when programming in Python

The RAFT Implementation I had to do utilizes sockets a fair amount, and most of these actor based services need to extensively use sockets and streaming

IO Bound Vs CPU Bound

A common misconception that should be addressed early is I/O bound and CPU bound workstreams

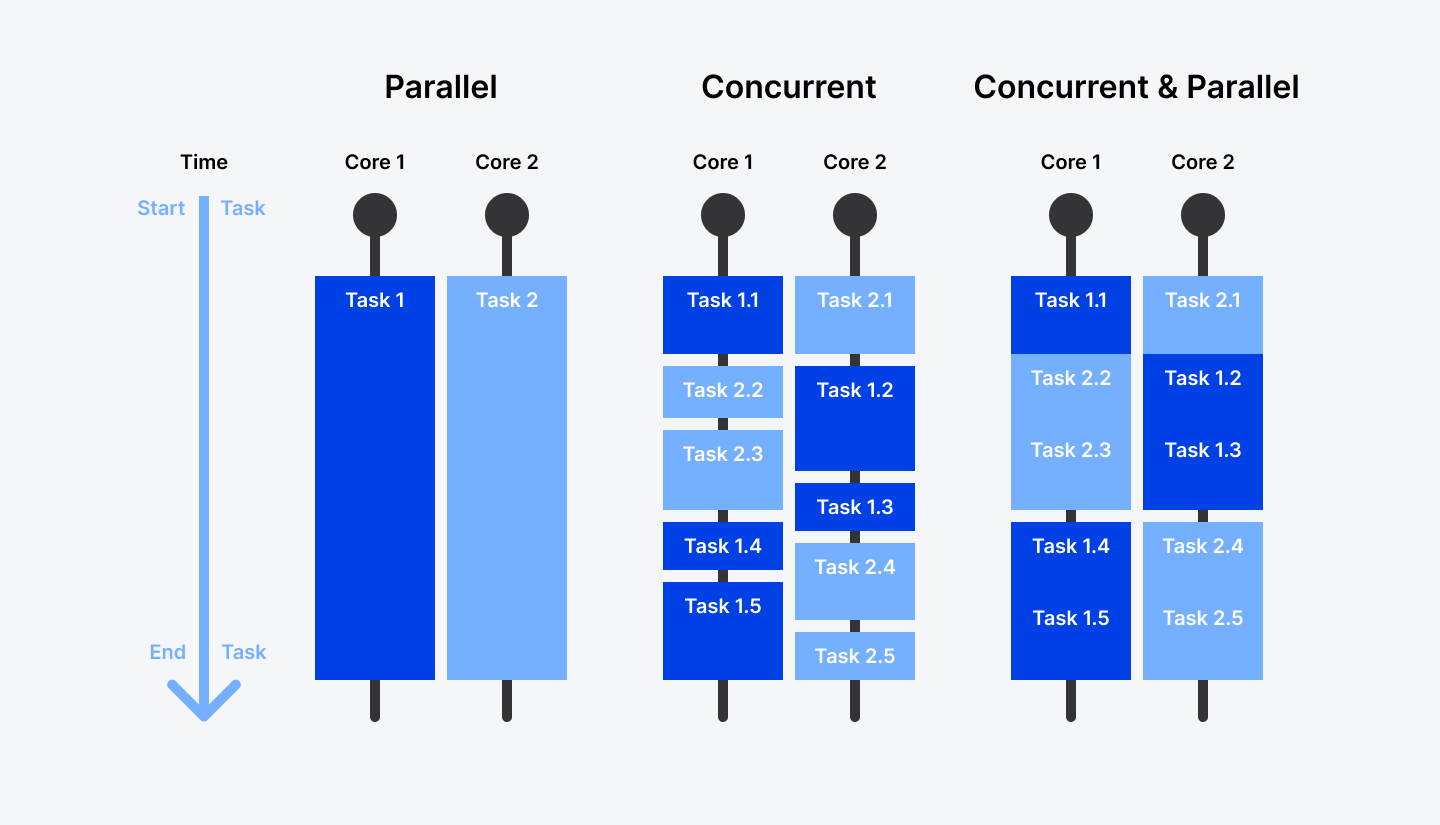

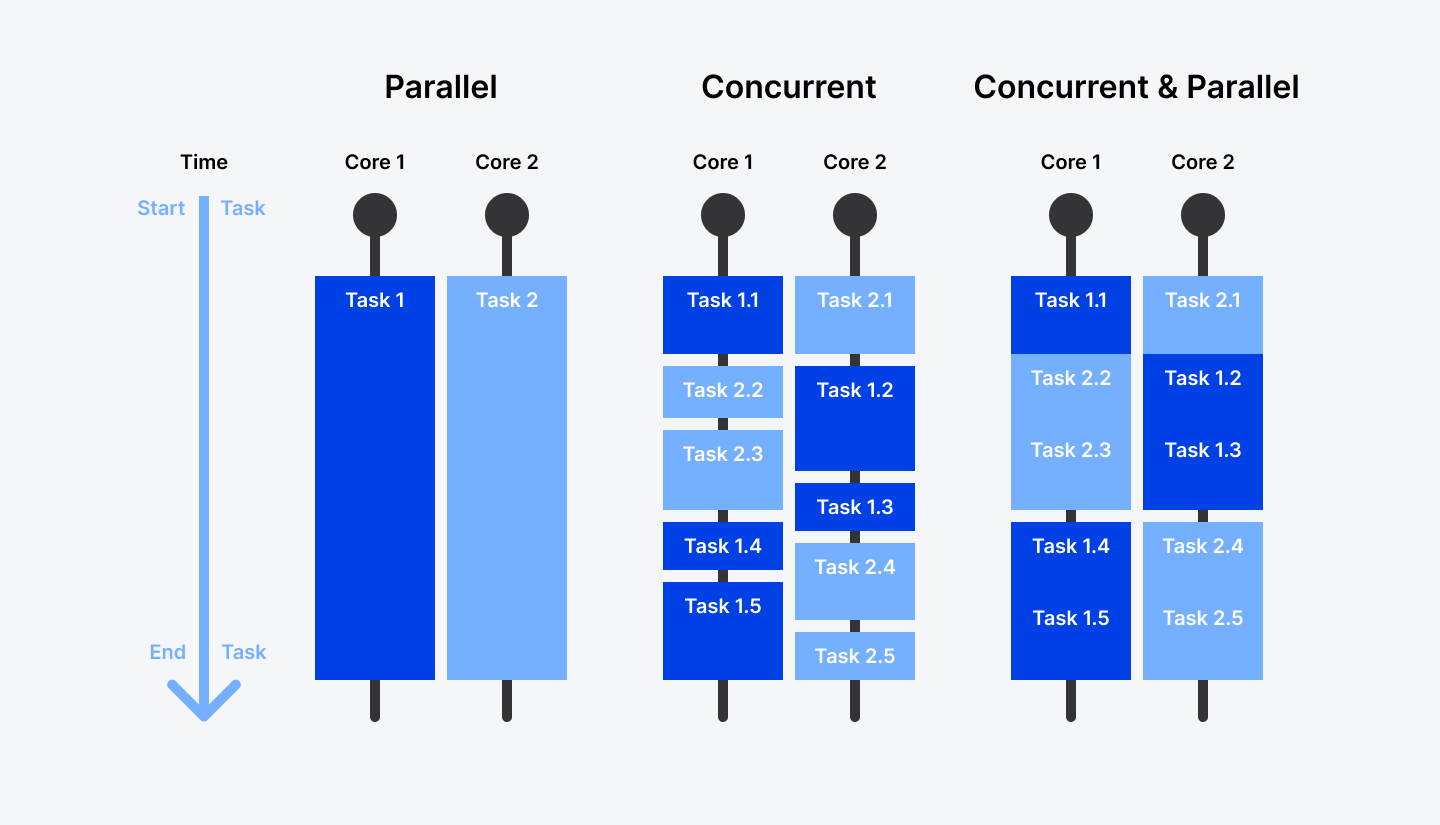

In any language, Python or Go or anything, I/O bound work is typically confronted using async concurrent frameworks - it's what allows you to handle hundreds of thousands of connections using 1 or 2 CPU's because a majority of the work is waiting on external calls, and all of the "inbetween time" can be spent handling other calls

CPU bound work like image processing can't have "inbetween time" - it needs all of the CPU to do the actual work, and so these can be confronted using multiple processes. If you have 4 CPU's, and a 256 pixel image, you can split up the image into 4 chunks of 64 pixels and process them in parallel on all 4 CPU's

Some applications like ML Inference are both I/O bound (database calls, feature store calls, traffic handlers) and CPU bound (matrix multiplication inference) - in these scenario's each of the different problems need to be handled separately

The TLDR is to utilize async concurrent threads for I/O bound work, and multi-processing (concurrent futures, ProcessPoolExecutor, or multiprocessing) modules for CPU bound work

Python Sockets

Python socket module specifically provides an interfact to typical Berkeley sockets API's like socket(), .bind(), .listen(), etc.. and these are all of the ways we can setup an IP:port API to send data to certain processes

These Python API's link directly to their C counterparts, and so utilizing the Python API's correctly can help to utilize all CPU's on a machine in an efficient manner via C

The socketserver module abstracts even more of this away, giving a set of easty to use API's to setup request-response echo type servers

Outside of these servers, there are other higher-level modules that support protocols like SMTP and HTTP

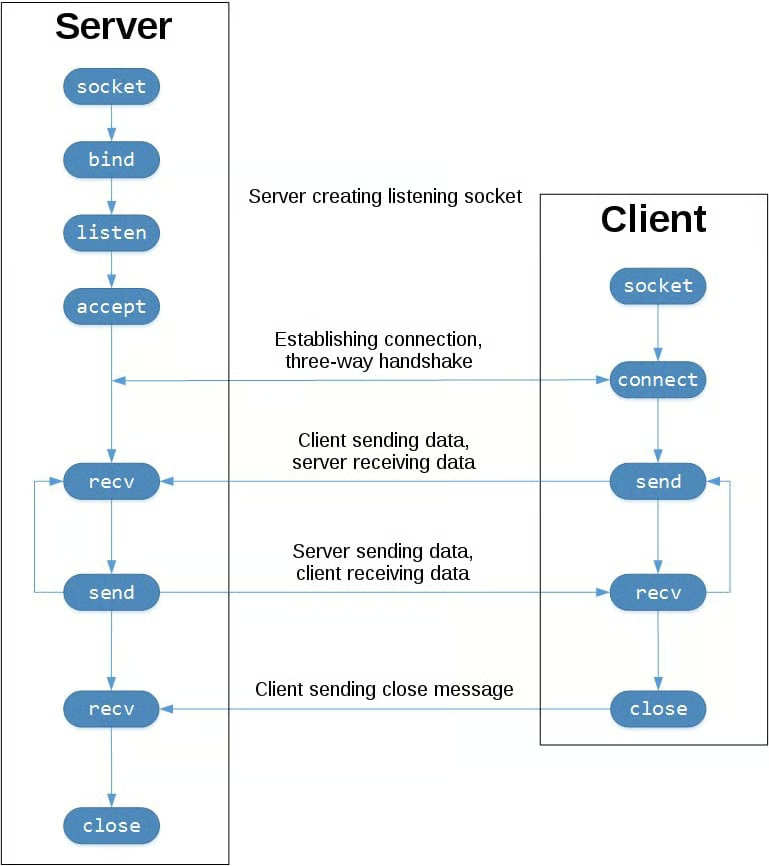

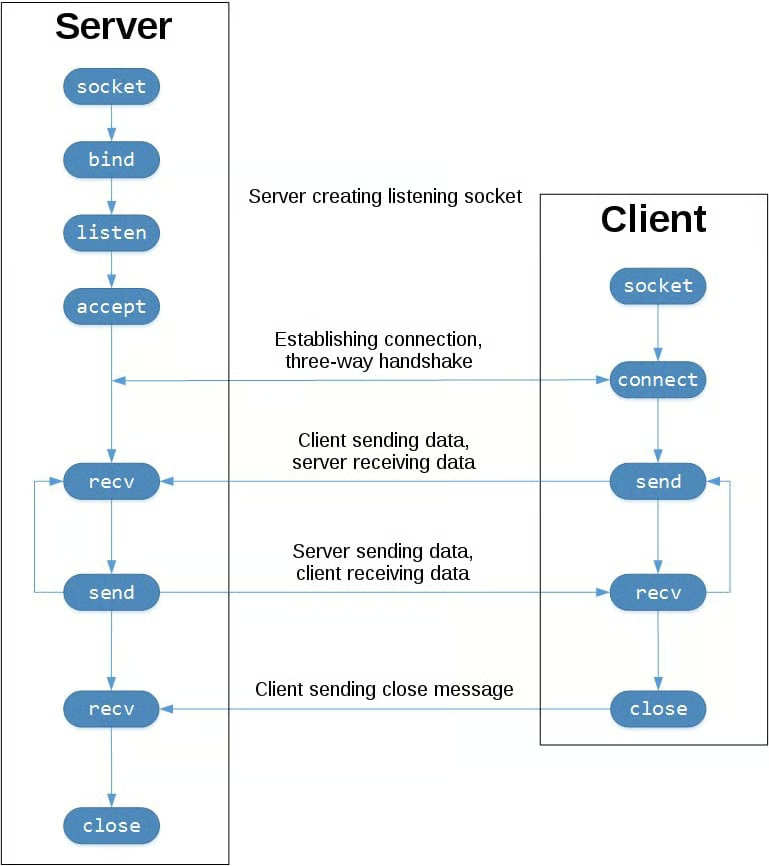

The image shown below also shows how we can utilize API methods to produce servers and clients

socket()initializes the socket.bind()will bind the socket to a specific port and Unix file descriptor.listen()starts the socket listening to connections from clients, and typically will do this in a non-blocking way (especially important in Python).accept()is necessary to call when a client actually connects- The client calls

.connect()to establish a connection and initiate a 3-way handshake - After the 3-way handshake is completed, both client and server are reachable and ready to communicate

- Data is sent and received using

.send()and.recv()calls- Programmer is responsible for formatting messages and ingesting / sending the correct amount of data - specifying

1024bytes to ingest means it will ingest maximum that many, or send out at most that data, but there's always edge cases to ingest more, loop and get more data, or format out some whitespace - Applications are responsible for checking that all data has been sent, and the application is responsible for re-attempting delivery if it's failed

- This is typically done via checksums over data packets

- Programmer is responsible for formatting messages and ingesting / sending the correct amount of data - specifying

- The client calls

- Then each server will

.close()their sockets and connections

Below is the Python code for an Echo Server

Show Python Script

import socket

HOST = "127.0.0.1" # Standard loopback interface address (localhost)

PORT = 65432 # Port to listen on (non-privileged ports are > 1023)

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

# socket context manager here ensures we don't have to call .close

# bind below will associate the socket with a specific network interface and port

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

# non-blocking way to listen for new connections - at this point the server is a listening socket

# you can specify a number of connections it can accept before refusing new ones

s.listen()

# accept blocks execution and waits for an incoming connection - once a client connects, it returns a new socket object representing the connection itself

# it's an entirely new socket object created from accept() - it's the one we use to communicate with the client

conn, addr = s.accept()

with conn:

print(f"Connected by {addr}")

while True:

# actually ingest data

data = conn.recv(1024)

if not data:

break

# send data back to connection

conn.sendall(data)

Some important distinctions from above:

connthat's created fromaccept()is an entirely new socket created that's specific to theserver-clientcommunication channel - it's different froms, and so if multiple clients connect toseach of them will have their own uniqueconn- The infinite

whileloop afterwards is what allows us torecvall data from a client, do something with it (nothing in echo server), and send it back to client without instantiating a new connection

- The infinite

Below is the Python code for an Echo Client - it's utilizing the same API's as the Server, but it is mostly just starting a connection to a known socket, and then starting to send and receive data

Show Python Script

import socket

HOST = "127.0.0.1" # The server's hostname or IP address

PORT = 65432 # The port used by the server

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.connect((HOST, PORT))

s.sendall(b"Hello, world")

data = s.recv(1024)

print(f"Received {data!r}")

If you run the 2 scripts above, when running python echo_server.py alone the terminal seems to hang, because it's stuck (blocked) on .accept() waiting for new incoming connections from a client. Once a client, such as python cho_client.py, is ran and started against it, the terminal will unblock

To check how things are progressing, you can utilize netstat which is available on most default OS, or lsof (listing open files), since sockets and open files are intertwined

Multiple Connections

So the above echo-server was great for handling one connection, but how to actually handle a webserver type scenario with hundreds or thousands of clients and connections

In discussion above there were some topics around send and recv with certain byte amounts and formatting, how can we ensure our specific vm-2-vm, i.e. client-2-server, connections are sending all data correctly back and forth to each other without sending to other groups? And how can we handle all of the state of our connections?

These are all handled by concurrent programming - concurrency is mimicing parallelism on one single thread, instead of truly parallel work being done. Python famously utilizes a global interpreter (GIL), and so each Python process is bound to a single GIL interpreter, and must use concurrent programming. There are ways to spawn multiple processes, each who have concurrent event handlers, and in that way we can utilize all cores on a machine, but that's discussed later on

To achieve concurrency in Python there's multiple options, and most overlap with each other in some ways:

- The most "bare bones" method is using

pthreads, which are just threads in Python, which can be stopped and started asyncIOpackage was introduced as a standard library, and allows developers to writeasync deffunctions that utilizeawait func()type syntax to stop a thread untilfunc()has returnd- The typical example is sending out a database query call that has an expensive join - if that join takes 10 seconds then

func()blocks for 10 seconds and other work can be done until it returns

- The typical example is sending out a database query call that has an expensive join - if that join takes 10 seconds then

- Concurrent Futures are high level interfaces for asynchronously executing functions using threads, they are comprised of Promises and Futures which can be viewed as awaitable functions that we expect to return at some point in the future

These are just a few ways of actually packaging up concurrent work, but communication between these threads or processes can involve files, queue's, inter-process queue's, local network socket communication, and other options

The scope of discussing all of this is beyond here, and a fair amount is talked through in the RAFT project and Building Async From Scratch Section

So, to get back to handling multiple connections, we can utilize anything above, and usually it involves higher level interfaces for handling multiple clients and using concurrent asynchronous workers

Instead of using select ourselves, you can usually just write asyncIO based functions and they handle the multiple communication problem for you

Even higher level interfaces like gevent, fastAPI, and some other 3rd party packages make this even easier

Lastly, we build out a multi-connection server under the select section

Most of the driving is done by the sel.select(), as it's blocking, waiting at the top of the loop for events, and is responsible for implementing the core event loop to wake up when read and write events are ready to be processed

Communication Breakdown

Most of the local communication done between processes is done via Loopback Interface, which is another name for 127.0.0.1 or localhost

Apps use loopback interface to communicate with other processes running on the same host, and for enhanced security measures from the external network

This is how machines that run webservers with their own private databases will setup connectivity - one or two CPU's are allocated to the database, and the rest allow the webserver to accept and process incoming request, while storing durable state on the database

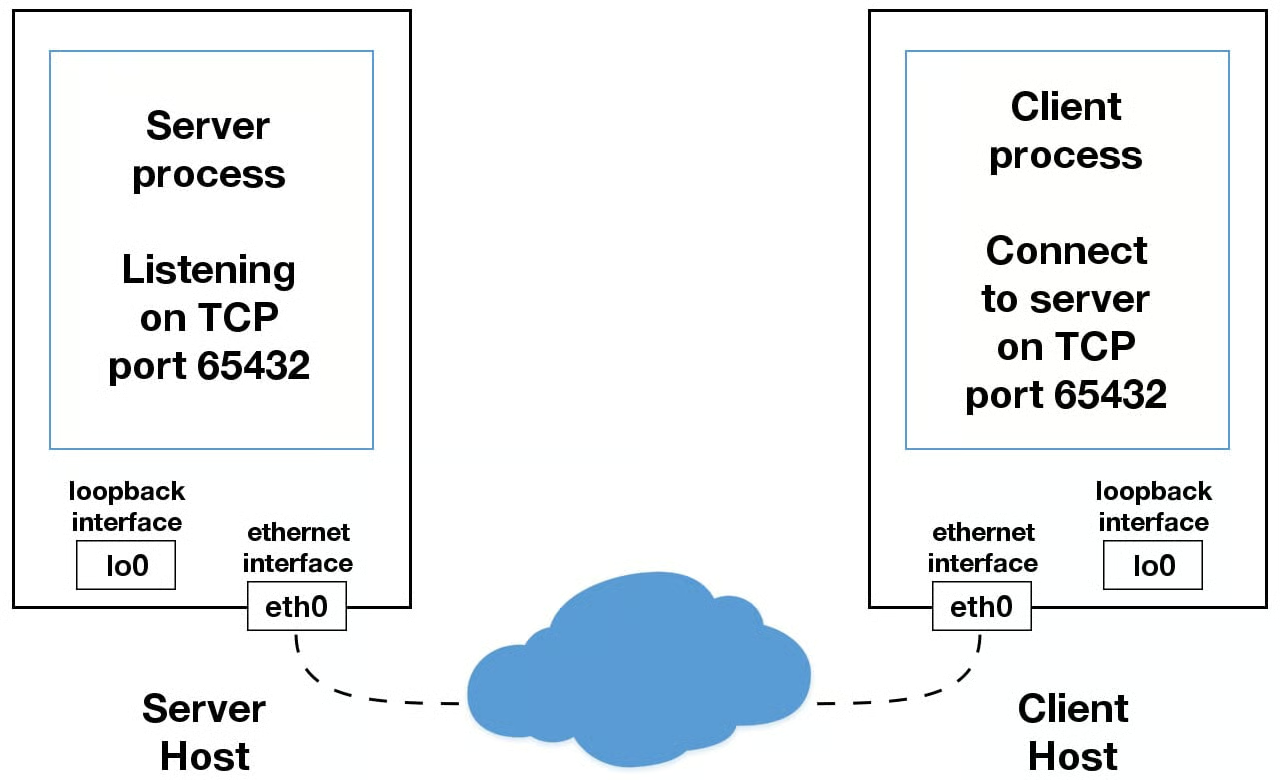

Utilizing an IP other than 127.0.0.1 means that it's most likely linking to the Ethernet Interface that's connected to an external network - this it the gateway to other hosts outside of "localhost"

Building Async From Scratch

Building an async framework from scratch is difficult, but is useful to understand how most of the higher level frameworks like asyncIO build on top of standard libraries (even though asyncIO is now a standard library), and then how even higher level interfaces like FastAPI build on top to help manage REST API's in Python

Select

.select(), the granddaddy of all system calls, is incredibly important throughout the networking universe - it allows you to check for I/O completion on more than one socket, so you can select() to see which sockets have I/O ready for reading and/or writing

The solution it solves is "in my one Python program, I need to loop over 1,000 different sockets and figure out which socket external process has returned". Essentially, if we are handling 1k clients connecting to our webserver, and each of those creates 2-3 database calls, we then have 1,000 + 2-3,000 external connections we need to keep track of - the 1k connections to client machines, and the 2k connections to an external database. How will we know which database calls have returned (some may be faster than others), and how do we know where to send the finalized results to? Select helps to solve the "which sockets have data ready for me to consume", or "which sockets have returned from calling the database for me to forward back to clients"

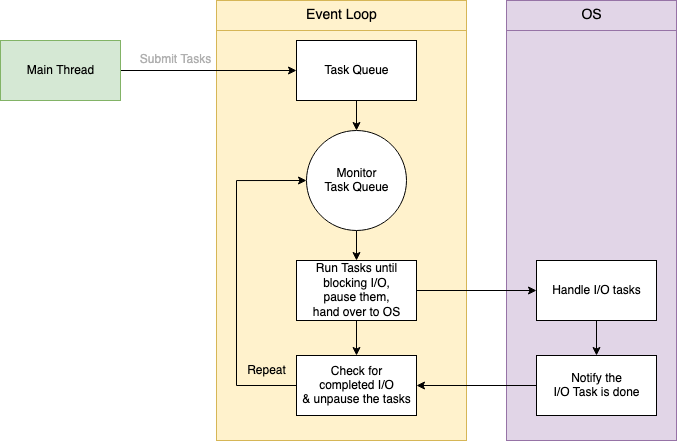

The selectors module in Python is the most efficient implementation that should work regardless of operating system that's used. Using select() by itself won't automatically run things concurrently, it's just a module for checking which sockets are ready for processing - the "typical" method utilized is an event loop, which basically just loops over all ready sockets and processes them sequentially, and then continuously loops and checks

asyncio for example, will use a single threaded cooperative multitasking and an event loop to manage tasks - below is a general "event loop" which just loops over all of the sockets we have access to, checks if they have data ready, and then for every ready socket we can receive data and put it into a callback queue (ingress queue below)

Show Python Script

def receive(self):

conn, addr = self.socket.accept()

logger.debug(f"receive - Connection from {conn} {addr} has been established!")

msg = self.socketInterface.recv_message(conn)

logger.debug(f"receive - Received message: {msg.data} on server {self.server_id} --> putting in queue")

self.ingress_queue.put(msg)

conn.close()

while True:

readable, _, _ = select([self.socket], [], [], self.NETWORK_TICK)

if self.socket in readable:

self.receive()

Select Multi Connection Example

Setting up the socket is the same as in most examples, but after that you'll need to configure the socket to be non-blocking and register selectors with it to handle in other threads

This allows us to wait for events on one or more sockets and then read and write data whenever it's ready

sel.register() registers the socket to be monitored with sel.select() for the events you're interested in

Show Python Script

import sys

import socket

import selectors

import types

sel = selectors.DefaultSelector()

# ...

host, port = sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[2])

lsock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

lsock.bind((host, port))

lsock.listen()

print(f"Listening on {(host, port)}")

lsock.setblocking(False)

sel.register(lsock, selectors.EVENT_READ, data=None)

We can store data in data which is returned whenever .select() returns - it's what we can use to keep track of what's being sent and receieved on the socket

To utilize any of this, we need an event loop - below the sel.select(timeout=None) will block until there are socket(s) ready for I/O - it'll return a list of tuples, one for each socket

- Each tuple contains a key and a mask

- Key is a

selectorKey- Contains a

fileobjattribute which is the actual socket object (file descriptor) itself - Also contains a

maskattribute which is an event mask of the operations that are ready- Masks are just bit masks representing things -

1001means first and fourth masks are ready, so there's a few event types that are displayed as binary masks

- Masks are just bit masks representing things -

datais another attribute that's a bit more special- If

key.dataisNone, then it means it's a listening socket and you'll need to accept the connection- We can do this with some sort of

accept_wrapper()function that handles accepting data, formatting it, etc..

- We can do this with some sort of

- If it's not

None, i.e. it has something, then it's a client socket that's already been accepted and we can service / process it- This is what the

service_connection()function is for

- This is what the

- If

- Contains a

Show Event Loops

try:

while True:

events = sel.select(timeout=None)

for key, mask in events:

if key.data is None:

accept_wrapper(key.fileobj)

else:

service_connection(key, mask)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("Caught keyboard interrupt, exiting")

finally:

sel.close()

The sock.accept() part in the accept_wrapper() is how we actually accept and read the incoming connection, and conn.setblocking(False) ensures that we don't block based on the socket - if it blocks then the entire server is stalled until it returns (until our call back to them returns), and other sockets are left waiting even though the socket isn't actually working

Show Accept Wrapper

def accept_wrapper(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept() # Should be ready to read

print(f"Accepted connection from {addr}")

conn.setblocking(False)

data = types.SimpleNamespace(addr=addr, inb=b"", outb=b"")

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

sel.register(conn, events, data=data)

data is an actual object to hold the data that you want included along with the socket, and that's passed to sel.register() with some other info which simply registers this socket and sets everything up to be a new connection we track with sel

The service_connection wrapper below is what's called once we actually want to handle an active socket - it basically will read in data if we've setup the mask to, and write it back out (echo)

We store the socket object itself in sock, and so sending the data back to that specific client is easy to handle, we don't have to look it up in a map or anything like that, we just get that info in the data structure. sock contains the object, and mask contains the events that are ready (the things we've decided to do / are ready to do in this socket)

Show Service Connection

def service_connection(key, mask):

sock = key.fileobj

data = key.data

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

recv_data = sock.recv(1024) # Should be ready to read

if recv_data:

data.outb += recv_data

else:

print(f"Closing connection to {data.addr}")

# Ensures our selector stops checking this socket

sel.unregister(sock)

sock.close()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

if data.outb:

print(f"Echoing {data.outb!r} to {data.addr}")

sent = sock.send(data.outb) # Should be ready to write

# Remove this data from buffer

data.outb = data.outb[sent:]

The full server implementation is below

Show Full Multi-Server

import sys

import socket

import selectors

import types

sel = selectors.DefaultSelector()

host, port = sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[2])

lsock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

lsock.bind((host, port))

lsock.listen()

print(f"Listening on {(host, port)}")

lsock.setblocking(False)

sel.register(lsock, selectors.EVENT_READ, data=None)

def accept_wrapper(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept() # Should be ready to read

print(f"Accepted connection from {addr}")

conn.setblocking(False)

data = types.SimpleNamespace(addr=addr, inb=b"", outb=b"")

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

sel.register(conn, events, data=data)

def service_connection(key, mask):

sock = key.fileobj

data = key.data

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

recv_data = sock.recv(1024) # Should be ready to read

if recv_data:

data.outb += recv_data

else:

print(f"Closing connection to {data.addr}")

sel.unregister(sock)

sock.close()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

if data.outb:

print(f"Echoing {data.outb!r} to {data.addr}")

sent = sock.send(data.outb) # Should be ready to write

data.outb = data.outb[sent:]

try:

while True:

events = sel.select(timeout=None)

for key, mask in events:

if key.data is None:

accept_wrapper(key.fileobj)

else:

service_connection(key, mask)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("Caught keyboard interrupt, exiting")

finally:

sel.close()

The Multi-Connection Client is very similar, and the only main difference is that the client keeps track of how much data it's sent and received so it can close the connection. Once it closes it's side, the server would also close it's socket

Below shows the small changes needed to service_connection to create the client

Show Multi-Connection Client Service Connection Diffs

def service_connection(key, mask):

sock = key.fileobj

data = key.data

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

recv_data = sock.recv(1024) # Should be ready to read

if recv_data:

- data.outb += recv_data

+ print(f"Received {recv_data!r} from connection {data.connid}")

+ data.recv_total += len(recv_data)

- else:

- print(f"Closing connection {data.connid}")

+ if not recv_data or data.recv_total == data.msg_total:

+ print(f"Closing connection {data.connid}")

sel.unregister(sock)

sock.close()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

+ if not data.outb and data.messages:

+ data.outb = data.messages.pop(0)

if data.outb:

- print(f"Echoing {data.outb!r} to {data.addr}")

+ print(f"Sending {data.outb!r} to connection {data.connid}")

sent = sock.send(data.outb) # Should be ready to write

data.outb = data.outb[sent:]

Show Multi-Connection Client

import sys

import socket

import selectors

import types

sel = selectors.DefaultSelector()

messages = [b"Message 1 from client.", b"Message 2 from client."]

def start_connections(host, port, num_conns):

server_addr = (host, port)

for i in range(0, num_conns):

connid = i + 1

print(f"Starting connection {connid} to {server_addr}")

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.setblocking(False)

# Raises different errors

sock.connect_ex(server_addr)

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

data = types.SimpleNamespace(

connid=connid,

msg_total=sum(len(m) for m in messages),

recv_total=0,

messages=messages.copy(),

outb=b"",

)

sel.register(sock, events, data=data)

...

So if we have 2 machines, Bob (IP address 0.0.0.1) and Alice (IP address 0.0.0.2), if Bob sets up a webserver on port 65000, and Alice has 3 main processes that will connect to it, then the Multi-Client script above will help establish this for her

Both Bob and Alice need to setup sockets, and actually Bob will setup 1 selector listening on some socket, and Alice will need to setup 3 sockets overall (1 per connection) where each of them try to talk to the same socket on Bob's server. Each pairing between an Alice socket and Bob socket is a connection, and so in total there are 3 connections that can all do request and response communication between Bob's server and Alice's processes

Proper Application Servers

Outside of the above there's a few other things that need addressing before the "server" could be considered complete

- Server depends on client behaving well

- Server crashes if any client interaction crashes

- No proper error codes or responses

- There are no timeouts, cleanups, or general "maintenance and upkeep" done on the server

- No formatting of messages for incoming byte streams

- We read in data via

recv(), but how do we know when the message is "ready" - If we miss some data, we can't run a seek over the missed data - it's simply missed (unless we save it somewhere)

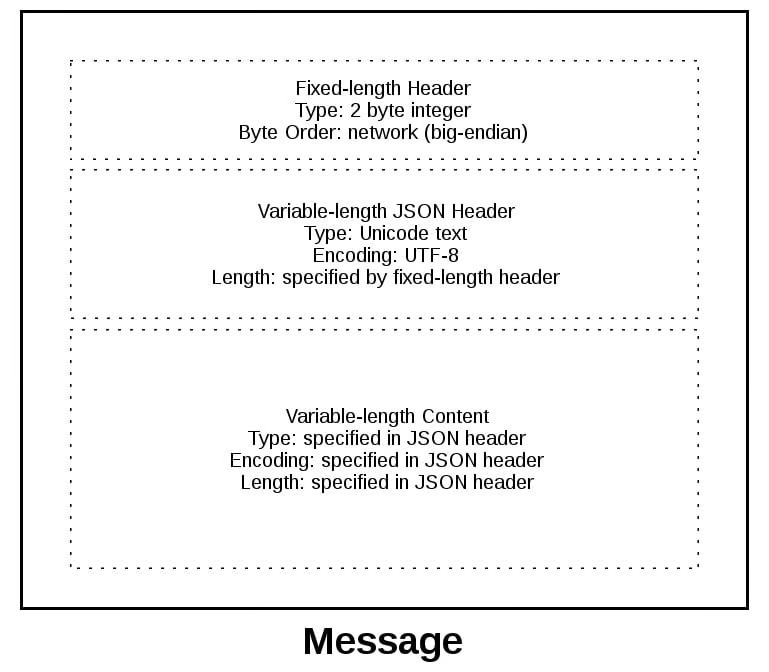

- This is where an application layer L7 protocol comes in - it helps us format raw bytes into coherent messages we can process

- After reading messages via

recv(), we need to keep up with how many bytes were read and figuring out where message boundaries, verifications, and lost data may be - This can be done with meta-information, fixed size messages (padding), etc - the header of HTTP messages are what typically solve this issue, and where header is a general fixed size and gives us the incoming message size we can use to read a dynamic length message

- After reading messages via

- Outside of formatting, there's byte order concerns as some OS's do little endian, and others do big endian, and so there's a number of concerns with processing raw bytes at the OS level

- UTF-8 eliminates some of these issues, and so utilizing UTF-8 for headers can typically resolve a majority of these issues

- The message payload itself can utilize any encoding, but headers typically use UTF-8

- We read in data via

So, from the above it's clear the L7 App Layer Protocol is probably the most important topic to cover along with general upkeep and maintenance

This is also a relevant discussion for Typical Load Balancers - an L4 load balancer will simply swap out destionation IP address information in TCP network packets, whereas L7 keeps multiple TCP socket connections between client and backend server. TCP has segments and they include source and destination IP addresses for networking infrastructure to forward, but HTTP headers are used so that applications can read dynamic length HTTP messages. NAT Translation happens from local private to public (or vice versa), and this happens on the actual router / load balancer before it forwards

Back to headers - to implement the L7 app protocol we will be utilizing some static headers so that we can send a dynamic payload. Some of the most used / often required headers are:

- byteorder: specifies the byte order of the machine (little or big)

- content-length: the length of the content, i.e. the dynamic message size, in bytes

- content-type: the type of content in the payload - text, json, binary, etc that can be used to decode or deserialize anything

- content-encoding: tied to content-type, this is the encoding used by the content like

utf-8for text orbinaryfor binary data

These headers inform the receiving party about the content in the payload of the message - most of the time these headers are in a dictionary, and are of a relatively common structure that can be assumed across different services (meaning there's a standard, so if you ever have to implement it you know what should be implemented so other people can use your service)

There's still one single problem of the length of the header - we can't always guarantee it's of a fixed size, and padding it to a known size isn't efficient and comes with other issues to solve for. So to solve this, usually the header size is sent pre-headers, and that's a fixed 2-byte pre-header (header header?) to prefix the JSON header and give it's length. Therefore the order of operations is:

- Send prefix-header that's a fixed 2-byte size containing the length of the headers

- Send headers, assumed to be that exact size

- Inside of the headers, there should be metadata and also a content-length header describing how large the payload is

- Send the payload itself

Show Message Object

class Message:

# ...

def read(self):

self._read()

if self._jsonheader_len is None:

self.process_protoheader()

if self._jsonheader_len is not None:

if self.jsonheader is None:

self.process_jsonheader()

if self.jsonheader:

if self.request is None:

self.process_request()

# ...

So at the end of this there will be sockets reading and writing, there are buffers being used to temporarily store data that's read in or written, and we are utilizing application layer protocols to ensure our binary data that's sent can be worked through by producer and consumer

Show Entire Message Client

import io

import json

import selectors

import struct

import sys

class Message:

def __init__(self, selector, sock, addr, request):

self.selector = selector

self.sock = sock

self.addr = addr

self.request = request

self._recv_buffer = b""

self._send_buffer = b""

self._request_queued = False

self._jsonheader_len = None

self.jsonheader = None

self.response = None

def _set_selector_events_mask(self, mode):

"""Set selector to listen for events: mode is 'r', 'w', or 'rw'."""

if mode == "r":

events = selectors.EVENT_READ

elif mode == "w":

events = selectors.EVENT_WRITE

elif mode == "rw":

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

else:

raise ValueError(f"Invalid events mask mode {mode!r}.")

self.selector.modify(self.sock, events, data=self)

def _read(self):

try:

# Should be ready to read

data = self.sock.recv(4096)

except BlockingIOError:

# Resource temporarily unavailable (errno EWOULDBLOCK)

pass

else:

if data:

self._recv_buffer += data

else:

raise RuntimeError("Peer closed.")

def _write(self):

if self._send_buffer:

print(f"Sending {self._send_buffer!r} to {self.addr}")

try:

# Should be ready to write

sent = self.sock.send(self._send_buffer)

except BlockingIOError:

# Resource temporarily unavailable (errno EWOULDBLOCK)

pass

else:

self._send_buffer = self._send_buffer[sent:]

def _json_encode(self, obj, encoding):

return json.dumps(obj, ensure_ascii=False).encode(encoding)

def _json_decode(self, json_bytes, encoding):

tiow = io.TextIOWrapper(

io.BytesIO(json_bytes), encoding=encoding, newline=""

)

obj = json.load(tiow)

tiow.close()

return obj

def _create_message(

self, *, content_bytes, content_type, content_encoding

):

jsonheader = {

"byteorder": sys.byteorder,

"content-type": content_type,

"content-encoding": content_encoding,

"content-length": len(content_bytes),

}

jsonheader_bytes = self._json_encode(jsonheader, "utf-8")

message_hdr = struct.pack(">H", len(jsonheader_bytes))

message = message_hdr + jsonheader_bytes + content_bytes

return message

def _process_response_json_content(self):

content = self.response

result = content.get("result")

print(f"Got result: {result}")

def _process_response_binary_content(self):

content = self.response

print(f"Got response: {content!r}")

def process_events(self, mask):

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

self.read()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

self.write()

def read(self):

self._read()

if self._jsonheader_len is None:

self.process_protoheader()

if self._jsonheader_len is not None:

if self.jsonheader is None:

self.process_jsonheader()

if self.jsonheader:

if self.response is None:

self.process_response()

def write(self):

if not self._request_queued:

self.queue_request()

self._write()

if self._request_queued:

if not self._send_buffer:

# Set selector to listen for read events, we're done writing.

self._set_selector_events_mask("r")

def close(self):

print(f"Closing connection to {self.addr}")

try:

self.selector.unregister(self.sock)

except Exception as e:

print(

f"Error: selector.unregister() exception for {self.addr}: {e!r}"

)

try:

self.sock.close()

except OSError as e:

print(f"Error: socket.close() exception for {self.addr}: {e!r}")

finally:

# Delete reference to socket object for garbage collection

self.sock = None

def queue_request(self):

content = self.request["content"]

content_type = self.request["type"]

content_encoding = self.request["encoding"]

if content_type == "text/json":

req = {

"content_bytes": self._json_encode(content, content_encoding),

"content_type": content_type,

"content_encoding": content_encoding,

}

else:

req = {

"content_bytes": content,

"content_type": content_type,

"content_encoding": content_encoding,

}

message = self._create_message(**req)

self._send_buffer += message

self._request_queued = True

def process_protoheader(self):

hdrlen = 2

if len(self._recv_buffer) >= hdrlen:

self._jsonheader_len = struct.unpack(

">H", self._recv_buffer[:hdrlen]

)[0]

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[hdrlen:]

def process_jsonheader(self):

hdrlen = self._jsonheader_len

if len(self._recv_buffer) >= hdrlen:

self.jsonheader = self._json_decode(

self._recv_buffer[:hdrlen], "utf-8"

)

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[hdrlen:]

for reqhdr in (

"byteorder",

"content-length",

"content-type",

"content-encoding",

):

if reqhdr not in self.jsonheader:

raise ValueError(f"Missing required header '{reqhdr}'.")

def process_response(self):

content_len = self.jsonheader["content-length"]

if not len(self._recv_buffer) >= content_len:

return

data = self._recv_buffer[:content_len]

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[content_len:]

if self.jsonheader["content-type"] == "text/json":

encoding = self.jsonheader["content-encoding"]

self.response = self._json_decode(data, encoding)

print(f"Received response {self.response!r} from {self.addr}")

self._process_response_json_content()

else:

# Binary or unknown content-type

self.response = data

print(

f"Received {self.jsonheader['content-type']} response from {self.addr}"

)

self._process_response_binary_content()

# Close when response has been processed

self.close()

Show Entire Message Server

import io

import json

import selectors

import struct

import sys

request_search = {

"morpheus": "Follow the white rabbit. \U0001f430",

"ring": "In the caves beneath the Misty Mountains. \U0001f48d",

"\U0001f436": "\U0001f43e Playing ball! \U0001f3d0",

}

class Message:

def __init__(self, selector, sock, addr):

self.selector = selector

self.sock = sock

self.addr = addr

self._recv_buffer = b""

self._send_buffer = b""

self._jsonheader_len = None

self.jsonheader = None

self.request = None

self.response_created = False

def _set_selector_events_mask(self, mode):

"""Set selector to listen for events: mode is 'r', 'w', or 'rw'."""

if mode == "r":

events = selectors.EVENT_READ

elif mode == "w":

events = selectors.EVENT_WRITE

elif mode == "rw":

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

else:

raise ValueError(f"Invalid events mask mode {mode!r}.")

self.selector.modify(self.sock, events, data=self)

def _read(self):

try:

# Should be ready to read

data = self.sock.recv(4096)

except BlockingIOError:

# Resource temporarily unavailable (errno EWOULDBLOCK)

pass

else:

if data:

self._recv_buffer += data

else:

raise RuntimeError("Peer closed.")

def _write(self):

if self._send_buffer:

print(f"Sending {self._send_buffer!r} to {self.addr}")

try:

# Should be ready to write

sent = self.sock.send(self._send_buffer)

except BlockingIOError:

# Resource temporarily unavailable (errno EWOULDBLOCK)

pass

else:

self._send_buffer = self._send_buffer[sent:]

# Close when the buffer is drained. The response has been sent.

if sent and not self._send_buffer:

self.close()

def _json_encode(self, obj, encoding):

return json.dumps(obj, ensure_ascii=False).encode(encoding)

def _json_decode(self, json_bytes, encoding):

tiow = io.TextIOWrapper(

io.BytesIO(json_bytes), encoding=encoding, newline=""

)

obj = json.load(tiow)

tiow.close()

return obj

def _create_message(

self, *, content_bytes, content_type, content_encoding

):

jsonheader = {

"byteorder": sys.byteorder,

"content-type": content_type,

"content-encoding": content_encoding,

"content-length": len(content_bytes),

}

jsonheader_bytes = self._json_encode(jsonheader, "utf-8")

message_hdr = struct.pack(">H", len(jsonheader_bytes))

message = message_hdr + jsonheader_bytes + content_bytes

return message

def _create_response_json_content(self):

action = self.request.get("action")

if action == "search":

query = self.request.get("value")

answer = request_search.get(query) or f"No match for '{query}'."

content = {"result": answer}

else:

content = {"result": f"Error: invalid action '{action}'."}

content_encoding = "utf-8"

response = {

"content_bytes": self._json_encode(content, content_encoding),

"content_type": "text/json",

"content_encoding": content_encoding,

}

return response

def _create_response_binary_content(self):

response = {

"content_bytes": b"First 10 bytes of request: "

+ self.request[:10],

"content_type": "binary/custom-server-binary-type",

"content_encoding": "binary",

}

return response

def process_events(self, mask):

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

self.read()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

self.write()

def read(self):

self._read()

if self._jsonheader_len is None:

self.process_protoheader()

if self._jsonheader_len is not None:

if self.jsonheader is None:

self.process_jsonheader()

if self.jsonheader:

if self.request is None:

self.process_request()

def write(self):

if self.request:

if not self.response_created:

self.create_response()

self._write()

def close(self):

print(f"Closing connection to {self.addr}")

try:

self.selector.unregister(self.sock)

except Exception as e:

print(

f"Error: selector.unregister() exception for {self.addr}: {e!r}"

)

try:

self.sock.close()

except OSError as e:

print(f"Error: socket.close() exception for {self.addr}: {e!r}")

finally:

# Delete reference to socket object for garbage collection

self.sock = None

def process_protoheader(self):

hdrlen = 2

if len(self._recv_buffer) >= hdrlen:

self._jsonheader_len = struct.unpack(

">H", self._recv_buffer[:hdrlen]

)[0]

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[hdrlen:]

def process_jsonheader(self):

hdrlen = self._jsonheader_len

if len(self._recv_buffer) >= hdrlen:

self.jsonheader = self._json_decode(

self._recv_buffer[:hdrlen], "utf-8"

)

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[hdrlen:]

for reqhdr in (

"byteorder",

"content-length",

"content-type",

"content-encoding",

):

if reqhdr not in self.jsonheader:

raise ValueError(f"Missing required header '{reqhdr}'.")

def process_request(self):

content_len = self.jsonheader["content-length"]

if not len(self._recv_buffer) >= content_len:

return

data = self._recv_buffer[:content_len]

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[content_len:]

if self.jsonheader["content-type"] == "text/json":

encoding = self.jsonheader["content-encoding"]

self.request = self._json_decode(data, encoding)

print(f"Received request {self.request!r} from {self.addr}")

else:

# Binary or unknown content-type

self.request = data

print(

f"Received {self.jsonheader['content-type']} request from {self.addr}"

)

# Set selector to listen for write events, we're done reading.

self._set_selector_events_mask("w")

def create_response(self):

if self.jsonheader["content-type"] == "text/json":

response = self._create_response_json_content()

else:

# Binary or unknown content-type

response = self._create_response_binary_content()

message = self._create_message(**response)

self.response_created = True

self._send_buffer += message