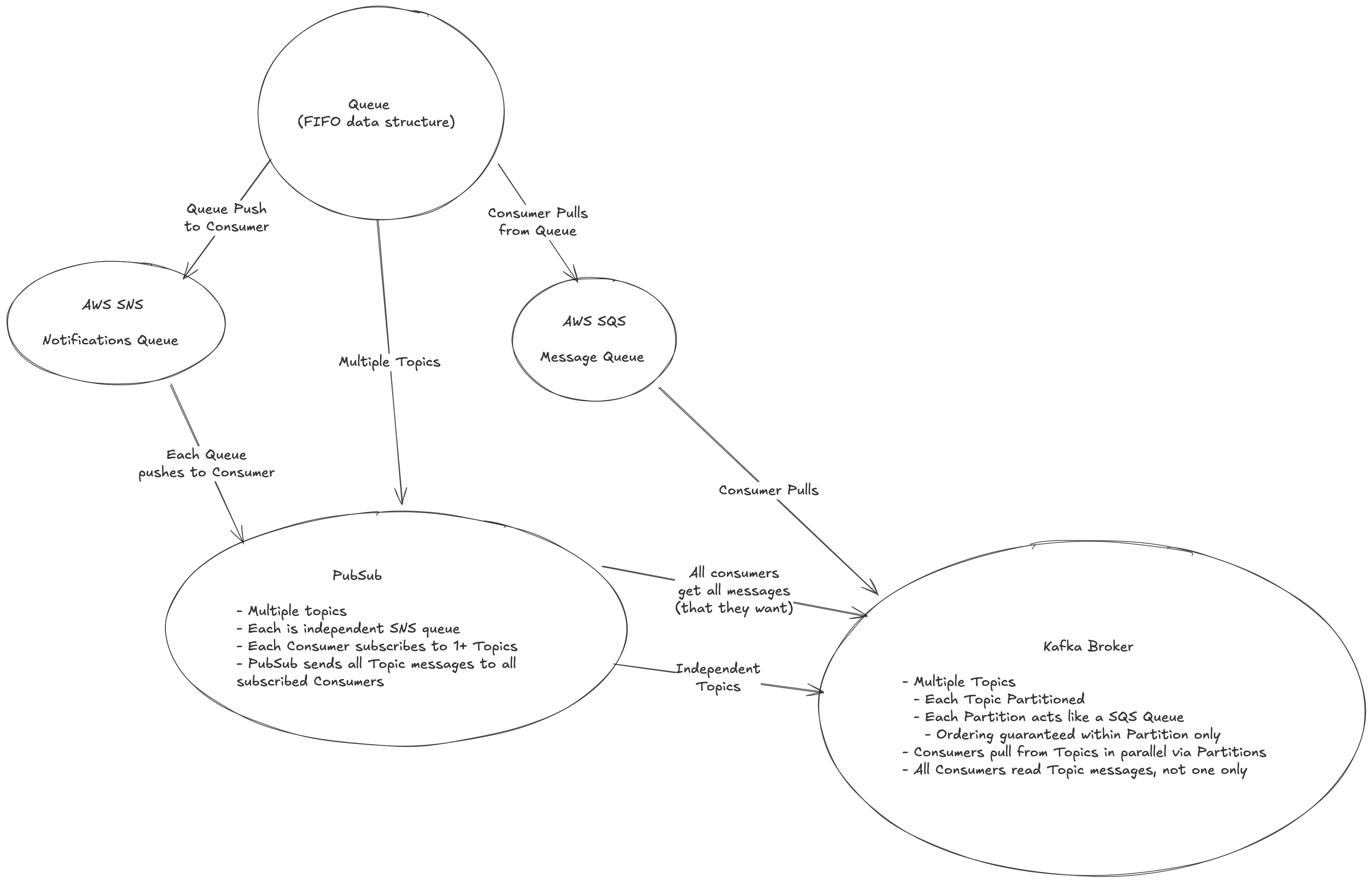

Queues

Queue's are generally used to ensure some sort of buffer between producers and consumers. They can be thought of as a place to keep messages between the two groups so that there's not overload or connectivity issues between the two sets

They also, generally, provide durability, single point connectivity, scaling, and other useful traits like priorities, acknowledgements, and retries

Queue's are useful when you have producers and consumers that have different workloads, where you might want to scale the consumers to comply with new messages coming in from producers - the most typical example I see is an API fielding requests and sending messages to workers to run complicated ML pipelines and models

Example:

- Message comes in with JSON field holding a document, or an S3 URL that holds a large text based document

- API fields the request, checks priority, and sends to a queue

- To ensure timely response, consumer pool may scale to 2-3x the size of the producer pool since each request is light on producer and very heavy on consumer

- Consumer may need to run multiple NLP pipelines such as Entity Extraction, Sentiment Analysis, and/or Categorization

Exactly Once FIFO Queues

Lots of references pulled from Sookocheff SQS Blog and Bravenewgeek Blog

FIFO (First-In-First-Out) queues are designed to ensure that messages are processed in the exact order they are sent and that each message is delivered exactly once

Achieving exactly once processing and strict ordering requires additional overhead compared to standard queues, which is why FIFO queues have some limitations and differences, and it also involves client side logic to ensure idempotency and correct failover handling

Synchronous Queues

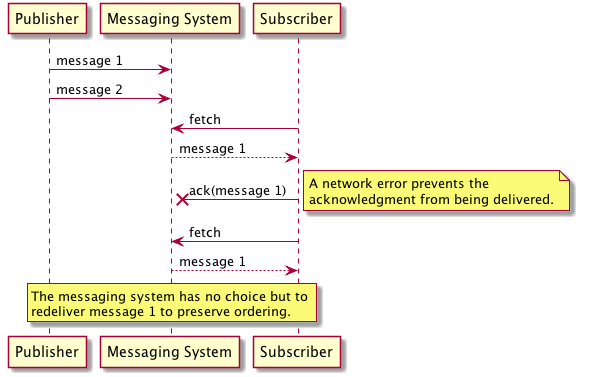

Typically a synchronous system is used to ensure messages are processed in order, and even single node queue so that there's no partitioning involved in the system. Even in this scenario, the guarantee ordering places a lot of constraints on scaling and throughput

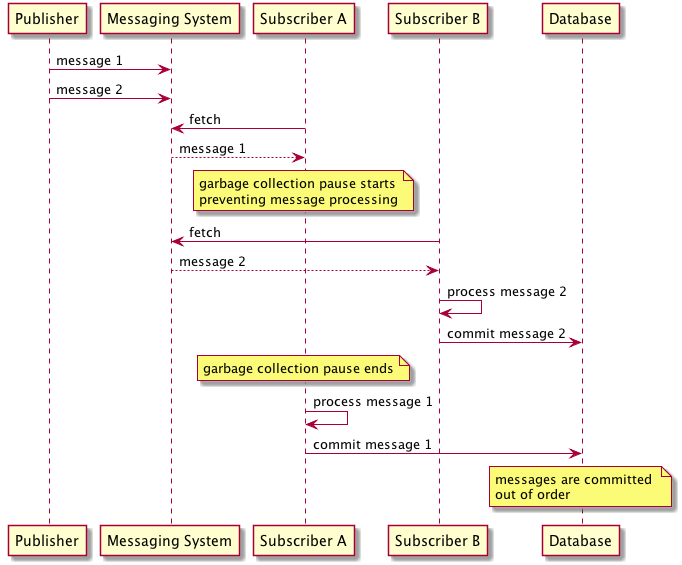

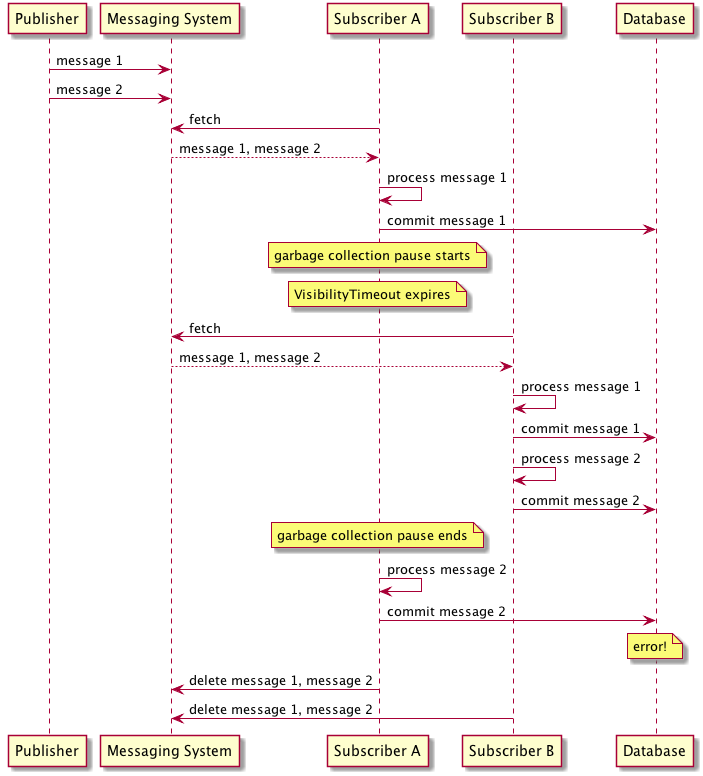

To preserve strict ordering, the queue cannot release or deliver a message until the previous message has been successfully processed and acknowledged by the consumer, which can be missed in multiple sections due to network failures, consumer crashes, or other issues. Throughput is also restricted to a single threaded receiver to ensure order is preserved - there can't be concurrent consumers pulling messages from the queue as this could easily break ordering. The below garbage collection example shows how random background processes can easily break ordering if multiple consumers are pulling from the queue

This same relation holds true for publishers - if multiple producers are sending messages to the queue concurrently, the queue must have a way to serialize these messages to ensure they are enqueued in the correct order. This often means that the queue must implement some form of locking or sequencing mechanism to manage concurrent writes, which can further limit throughput and scalability, or the producers need to somehow coordinate themselves which is often not feasible

Therefore, the conclusion we can reach is FIFO is only meaningful in a single-threaded publisher and receiver model, which severely limits scalability and throughput

AWS SQS FIFO Queues

In AWS SQS FIFO implementation, ordering is applied on a per MessageGroupID basis - meaning that messages with the same MessageGroupID are guaranteed to be processed in order, but messages with different MessageGroupIDs can be processed out of order relative to each other - it's very similar to Kafka Partitions Ordering in that sense

This allows for some level of parallelism and scalability, as messages with different MessageGroupIDs can be processed concurrently by multiple consumers, while still preserving ordering within each group. It also allows users to pull different levers to scale consumers based on the number of MessageGroupIDs they have

When a message is publishes to a specific MessageGroupID, SQS ensures that all messages with that same MessageGroupID are delivered to consumers in the order they were sent. This is achieved by maintaining a separate queue for each MessageGroupID internally, and ensuring that messages are processed sequentially within each group, and on writes locking the actual MessageGroupID so that only one producer can write to it at a time

- Publishing to a single

MessageGroupIDwill ensure strict ordering, but will limit throughput to a single consumer processing messages from that group - Publishing to multiple

MessageGroupIDs allows for concurrent processing by multiple consumers, increasing throughput - Publish every single message to its own

MessageGroupIDto maximize parallelism, but this sacrifices ordering guarantees (there is no ordering at all)

Within each message group you're essentially running a synchronous queue, so the same limitations apply - single threaded consumer per MessageGroupID, and throughput is limited by the slowest consumer processing messages from that group. This doesn't mean you can't have multiple actual VM's writing to the same MessageGroupID, but SQS itself as a service will serialize those writes to ensure ordering is preserved. I was a bit caught up on this - if you have multiple VM's that are running some SaaS application that all write to the same MessageGroupID, then hypothetically you could have 2 VM's trying to write to the same MessageGroupID at the same time - SQS will simply serialize those writes internally to ensure ordering is preserved, but this could lead to increased latency and reduced throughput as the queue manages concurrent writes. This is no longer a single-threaded publisher, but you'll need to consider the implications and potentially utilize sticky sessions or something else to ensure that a single VM is writing to a specific MessageGroupID if ordering is mission critical, and if not then there's a chance 2 events could be written out of order if something happens between the 2 writes (similar to the garbage collection example above)

The single-threaded part is that there's only 1 "thread" in SQS that is writing to that MessageGroupID at any given time, even if multiple producers are trying to write to it concurrently

The Blog from Sookocheff actually mentions this explicitly:

In conclusion, SQS’s implementation of FIFO queues support ordering guarantees at limited throughput per message group. In practice, this means certain design restrictions for both message publishers and message consumers. When publishing, you have to design your application to only have one publisher per message group. If your application is designed to be horizontally scalable and fronted by a load-balancer, this may not be as simple as it sounds. As an example, if you design your application to group messages by a user identifier, you must ensure that all messages being published for that identifier are being published by the same application instance using some form of sticky-routing, or by coordinating publishes between instances using a transactional storage system. When subscribing to messages, the situation is simpler because SQS will only deliver messages to subscribers in order. In practice, this means you can have multiple subscribers consuming from a group but only one consumer will be actively consuming messages from a message group at a time while others remain idle.

Exactly Once

Achieving exactly-once processing is a whole other beast. Most messaging systems, including standard queues, typically provide at-least-once delivery guarantees, meaning that messages may be delivered more than once in certain failure scenarios. If you have idempotent messages then this is not a problem, but if you need strict exactly-once processing, additional synchronous message deduplication mechanisms are required

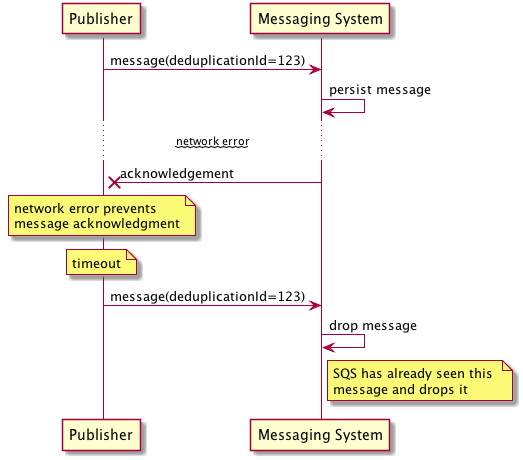

In AWS SQS FIFO queuees, exactly-once processing is achieved by queue's working together with publisher API's to avoid introducing duplicate messages. When a message is sent to a FIFO queue, the publisher can include a MessageDeduplicationId, which is a unique identifier for that message. SQS uses this ID to track messages that have been sent within a 5-minute deduplication interval. If a message with the same MessageDeduplicationId is sent again within this interval, SQS will ignore the duplicate message and not deliver it to consumers. This helps to prevent missed acknowledgements or network failures from causing duplicate message processing

This is only exactly-once within the 5 minute deduplication interval, and so if duplicate messages are sent outside of this interval they can be duplicated. Additionally, if the publisher does not provide a MessageDeduplicationId, SQS will generate one based on the content of the message body using a SHA-256 hash. This means that if two messages have the same content and are sent within the deduplication interval, they will be considered duplicates and only one will be delivered! This means it was zero times delivered, or potentially 2 times delivered!

- 0 times delivered if the same message is sent twice within the deduplication interval and SQS ignores the duplicate (same message like button click from client phone app)

- 1 time delivered if the message is sent once

- 2 times delivered if the same message is sent twice outside of the deduplication interval

To solve the 0 times delivered, the publisher should generate a unique MessageDeduplicationId for each message, even if the content is the same. This can be done using a combination of a unique identifier (like a UUID) and a timestamp to ensure uniqueness

To solve the 2 times delivered, specifically outside of the deduplication interval, the consumer must implement idempotent processing logic. This means that the consumer should be able to handle duplicate messages gracefully without causing unintended side effects. This can be achieved by maintaining a record of processed message IDs and checking against this record before processing a new message - this is similar to what AWS does in the 5 minute interval, but realistically it's the only way to ensure true exactly-once processing

FIFO queue's can't guarantee exactly once delivery, as it's provably impossible to achieve in a distributed system without some form of external coordination or state management. Even if a subscriber receives a message from the transport layer (queue), there's no guarantee it can process the message without a crash in which case you'd desire the messaging system to redeliver the message, leading to potential duplicates

AWS SQS FIFO guarantees exactly-once processing by guaranteeing that once a message has been successfuly acknowledged as processed, then it won't be delivered again

AWS SQS FIFO Message Consumption

To drive the example home it's easiest to show how things should be done

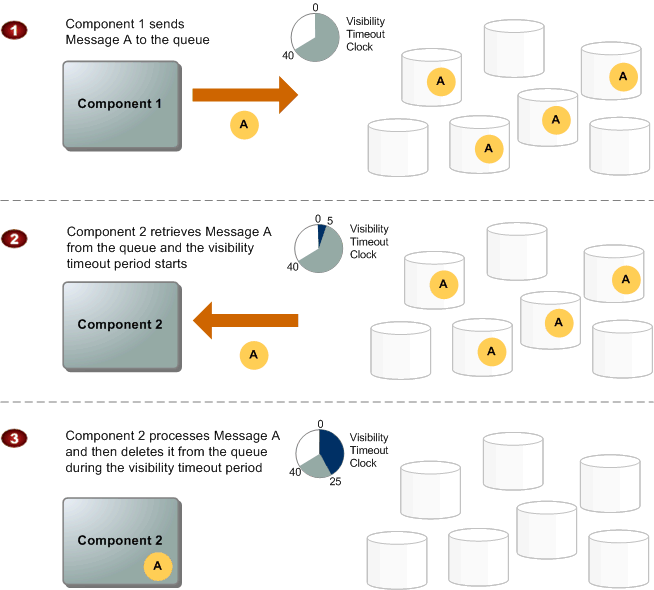

When a consumer receives and processes a message from a queue, the message remains in the queue marked as "invisible" for a specified visibility timeout period. SQS has no knowledge of the consumer system, so it has no guarantee that the consuming system has processed the message. Therefore, SQS requires the consumer explicitly deletes the message from the queue (essentially an acknowledgement) after successfully processing it. If the consumer fails to delete the message within the visibility timeout period, the message becomes visible again in the queue and can be redelivered to another consumer. To ensure FIFO processing, SQS guarantees that messages with the same MessageGroupID are delivered to consumers in the order they were sent. This means that if a message is redelivered due to a visibility timeout expiration, it will be delivered after all previous messages in the same group have been successfully processed and acknowledged. If a message in a MessageGroupID is being processed by one consumer and it's visbility timeout period is 30 seconds, it will wait the full 30 seconds before redelivering the message to another consumer, even if the first consumer crashes immediately after receiving the message. This ensures that messages are processed in order, but it can lead to increased latency and reduced throughput if consumers are slow or unreliable

This means the visbility timeout period acts as a TTL on a lock - if the consumer doesn't delete the message within that period, the lock expires and the message can be redelivered. Therefore, it's crucial to set an appropriate visibility timeout based on the expected processing time of messages to balance between timely redelivery and avoiding premature message reprocessing

"Now, suppose a subscriber receives a batch of messages and begins processing them, committing the result to a database. Unfortunately, halfway through processing the subscriber halts because of a garbage collection pause, failing to delete the messages it has processed before the visibility timeout expires. In that case, the messages would be made available to other consumers, which might end up reading and processing duplicates."

So processing messages in a batch any writing to a database means each write / batch must be idempotent and able to be rolled back - even with a single consumer if you process a message and then fail to delete the message, it will be redeliveered and processed again

Therefore, FIFO SQS queue's offer exactly-once processing only if:

- Publishers never publish duplicate messages wider than the 5 minute deduplication interval

- Consumers never fail to delete the messages they have processed from the queue

- In practice this means consumers need to read messages one at a time, process them, delete them, and then move to the next message

- Some blogs mention the consumers must durably store messages on their own storage systems before deleting them from the queue to ensure no messages are lost, but this is only needed if idempotency is not possible

These topics are similar to Atomic Broadcast in Distributed Systems, and the Two Generals Problem - achieving exactly-once processing in a distributed system is inherently difficult due to the possibility of failures at any point in the process, and requires 2 safety properties:

- Reliable delivery - If a message is delivered to one node, it is delivered to all nodes

- Totally ordered delivery - All nodes deliver messages in the same order

FIFO is stronger than this Atomic Broadcast as well because it also requires ordering across delivery - any order will do in atomic broadcast, as long as it's the same across all nodes

This also goes back to consensus, WAL's, and distributed databases - achieving exactly-once processing in a distributed system. The blog actually recommends to utilize databases or commit logs instead of FIFO queue's, as they are better suited for this type of workload

When in-order and exactly-once messaging looks like a good solution to your problem, consider using the same datastore as an alternative that is usually simpler, more performant, and less error prone.

Queues In The Wild

Some examples below of queue's typically used "in the wild"

SQS

SQS is just a standard message queue service from AWS that allows you to send messages between producers and consumers, but there are a few different types of queues:

- Standard Queues: The default type of SQS queue that offers high throughput, best-effort ordering, and at-least-once delivery

- You must design your application to handle potential duplicate messages and out-of-order delivery

- At least once delivery means that a message might be delivered more than once, so your consumer logic should be idempotent to handle duplicates

- Messages are invisible to other consumers for a specified visibility timeout period after being received, allowing the consumer to process the message without interference

- Messages are generally delivered in the order they are sent, but this is not guaranteed

- Messages must be deleted from the queue by the consumer after processing to prevent them from being received again

- You can mark messages with a

MessageGroupIDto ensure ordering within that group, but across groups there's no ordering guarantee

- You must design your application to handle potential duplicate messages and out-of-order delivery

- FIFO Queues

- Designed to ensure that messages are processed in the exact order they are sent and that each message is delivered exactly once

- FIFO queues use a combination of message deduplication IDs and message group IDs to achieve this

Redis

RabbitMQ

Celery

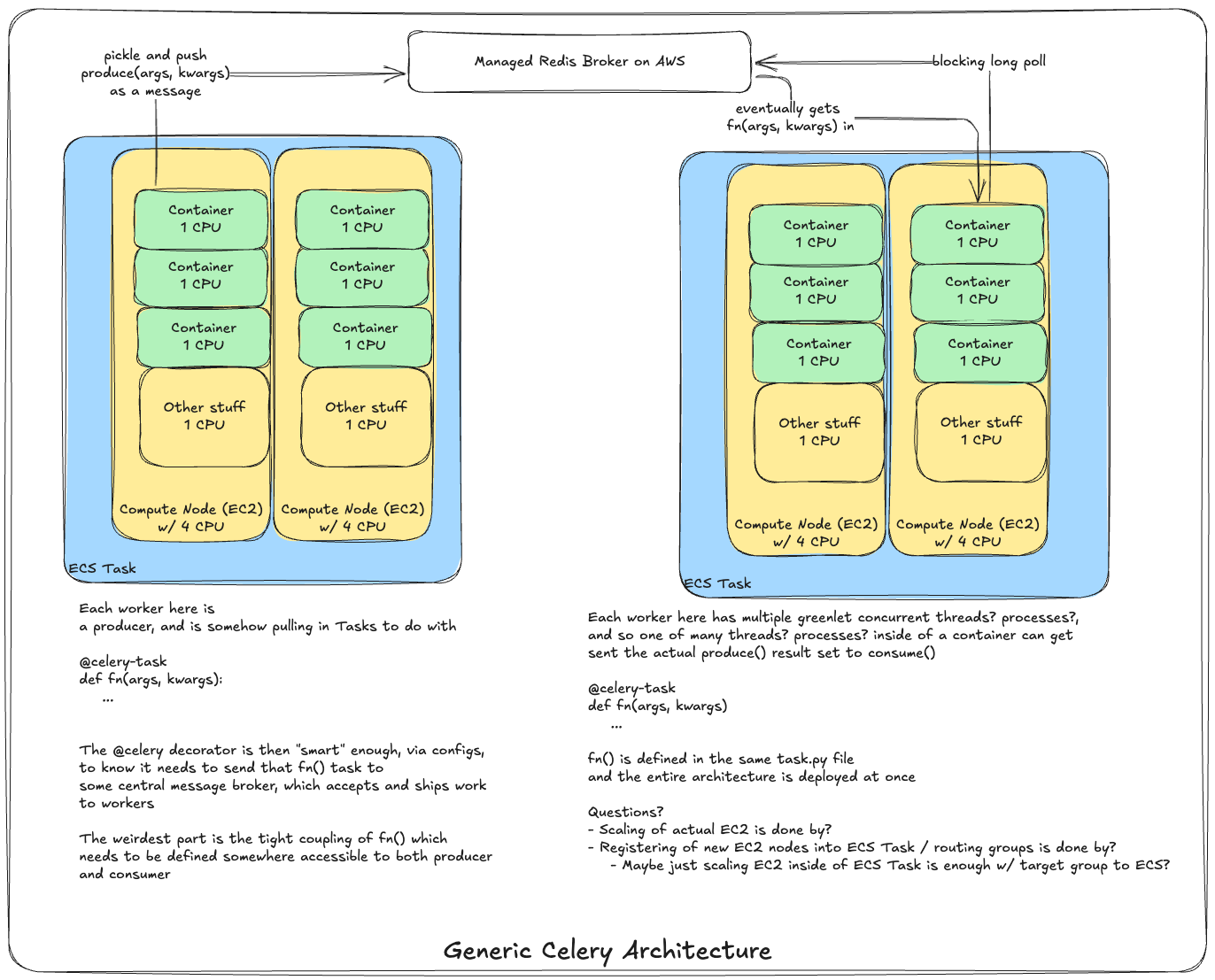

Celery is somewhere between a queue, a message broker, and a serializable function passer - Celery, IMO, is not actually a queue, but it's often described as one

At it's core, Celery is probably best described as an Distributed Producer-Consumer Architecture SDK or something in that vein

Celery helps developers to write tightly coupled producer.py and consumer.py scripts, along with celery.config files, which allow producers to push to a backend message queue, typically Redis or RabbitMQ, which then gets pulled by consumers

Celery sits at the application plane, and it's "scaling" is done on Celery Workers which are tightly coupled to the compute / infra plane

Celery cannot ask your infra plane to stand up more computes, it can simply scale up more processes on each of those computes

Celery Structure

Celery has a few core components that make it work

- Brokers - The message queue that Celery uses to pass messages between producers and consumers - typically Redis or RabbitMQ

- Producers - The code that produces tasks and sends them to the broker

- Consumers - The code that consumes tasks from the broker

- Consumers are the actual workers that process the tasks, and they typically run in separate processes or containers

- You do not specifically create a

consumer.pyfile, your producers calltasks.add.delay()and then eventually they will get a returned result - Therefore, our producers call a worker and then consume the output

- Workers - The processes (actual computes) that run the consumer code and execute the tasks

- Tasks - The functions that are executed by the workers (and passed between producers and consumers)

These components work together to create a distributed task queue system that allows for asynchronous task execution and scaling, BUT they are also tightly coupled in terms of repo setup, and code structure

In a typical setup, there are 3 main components

Tasks / App

tasks.py- This file contains the Celery app configuration and the task definitions. Both producers and consumers will import this file to access the Celery app and tasks- This file is the "glue" that holds the producer and consumer code together, and so it tightly couples your sender (producer) and receiver (consumer)

- A number of implementations will make this a proper separate package that both producer and consumer repos can import

The Celery() instance below is commonly referred to as the "Celery app"

from celery import Celery

app = Celery('tasks', broker='pyamqp://guest@localhost//')

@app.task

def add(x, y):

return x + y

- After this, you're able to run Celery via

celery -A tasks worker --loglevel=INFO- Form:

celery -A <module_name> <type> --loglevel=INFO - A crap load of other CLI options for running as daemon, setting up worker pools, etc...

- Form:

You can even have multiple Celery Apps and Brokers inside of a Project

from celery import Celery

app1 = Celery('app1', broker='redis://localhost:6379/0')

app2 = Celery('app2', broker='amqp://guest@localhost//')

@app1.task

def task_a():

pass

@app2.task

def task_b():

pass

Calling The Task

Calling an actual task simply involves importing the module in tasks.py and running the .delay() method

In our tasks module, since there's a broker involved, what ends up happening is this task gets scheduled on our broker (queue), and the worker pool will pick it up for execution

from tasks import add

result = add.delay(4, 4)

Results

The results backend stores state of tasks running

You can use Mongo, SQLAlchemy + DJango, Redis, or even use RPC to send things back to the broker to go back to the consumer / producer

From above, you can then call something like

result.ready() # True or False

Configuration

From the Celery Docs: "The input must be connected to a broker, and the output can be optionally connected to a result backend."

Things are mostly this simple

Then it says "However, if you look closely at the back, there’s a lid revealing loads of sliders, dials, and buttons: this is the configuration."

Because Celery has a ton of stuff to tweak to make things actually run in parallel with proper CPU saturation - are your tasks I/O bound, or CPU bound? Are there certain datasets and volumes that need to be attached? How does everything interact with the backend results set? How are retries done?! Etc

In large scale use cases, there are entire configuration modules with routing + task definitions

celeryconfig.py

broker_url = 'pyamqp://'

result_backend = 'rpc://'

task_serializer = 'json'

result_serializer = 'json'

accept_content = ['json']

timezone = 'Europe/Oslo'

enable_utc = True

task_routes = {

'tasks.add': 'low-priority',

}

task_annotations = {

'tasks.add': {'rate_limit': '10/m'}

}

Examples

I/O Bound Task

Let's say you have a setup where you have an API request that comes in, like for a user registration, and the API needs to call a handle() function that:

- Creates a new user

- Creates their profile and setting configuration

- Queue's a welcome email in SQS

- And finally, after ensuring all of these are done, returns a response to the user

In this scenario, you can have a lightweight FastAPI in front that accepts new requests and calls a task.handle() function that does everything

The actual workers themselves would be I/O bound, and running on the Celery worker pool, so how does everything look?

src/

├── tasks.py

└── main.py

# tasks.py

from celery import Celery

app = Celery('tasks', broker='pyamqp://guest@localhost//')

@app.task

def handle(user_id):

async new_user(user_id)

async new_profile(user_id)

async new_settings(user_id)

@app.task

async def new_user(user_id):

await call_database(user_id, CREATE_USER)

@app.task

async def new_profile(user_id):

await call_database(user_id, CREATE_PROFILE)

@app.task

async def new_settings(user_id):

await call_database(user_id, CREATE_SETTINGS)

from tasks import handle

app = FastAPI()

@app.post("/create")

def create_add_task(user_id: int):

result = handle.delay(user_id)

return {"task_id": result.id}

From here, any API call to /create will enqueue a new task for processing the user creation workflow. The FastAPI application will immediately respond with the task ID, allowing the client to check the status of the task later if needed

Some people will do the following:

@app.post("/create")

async def create_add_task(user_id: int):

result = await handle.delay(user_id)

return {"task_id": result.id}

Which will block until the task is finished and return the result directly to the client. This approach is generally not recommended for long-running tasks, as it defeats the purpose of using a task queue. Instead, it's better to return the task ID immediately and let the client poll for the result later.

delay() isn't an async function, and doesn't return an awaitable so you can't use await with it.

AsyncResult.get() is truly async call, and can be awaited - most documentation talks about not doing this because "task queue could take a long time to return a result, and you don't want to block your application while waiting for it."

While an event loop (like in FastAPI) can handle other requests while awaiting, the user’s request is still "pending" until the task is done. The main benefit of a task queue is to decouple the request/response cycle from the background work, allowing you to return immediately and let the client poll for the result

Therefore, if you're truly using Celery for I/O bound work you will most likely have to return taskID to the client and let them poll for the result.

@app.post("/create")

async def create_add_task(user_id: int):

result = handle.delay(user_id)

return {"task_id": result.id}

@app.post("/result/{task_id}")

async def get_task_result(task_id: str):

result = AsyncResult(task_id)

if result.ready():

return {"status": "completed", "result": result.get()}

else:

return {"status": "pending"}